I had several jobs during my youth besides the paper route. I helped to bale hay, hoed or walked beans, detasseled corn, worked at the local Lake’s and Earl May Seed and Nursery and cleaned hog pens. It seems like when I was old enough, I always had a summer or weekend job. Probably a good thing as I loved to go to the local Five and Dime stores and feed my habit of collecting Matchbox cars and other trinkets or spur of the moment purchases such as goldfish. I am going to take a bit of a departure from the paper route for Part 2 and discuss the various jobs I had during my youth.

Baling Hay

Baling hay was never easy work. First the cut hay had to be raked and fed through the baler, where the machine packed it into tight, square bundles bound with twine. Those bales would tumble out the back, and my job was to grab them and stack them on the wagon as it jolted and bounced across the field. Each one was heavy, scratchy, and awkward to lift—especially as the pile grew higher and you had to heave them overhead.

I’ll never forget my first job baling hay. I was just riding along with Dad in the fuel truck, tagging along on a delivery to Lowell Baker’s farm. Whenever Lowell was around, he’d come over to the truck to chew the fat with Dad—complain about the weather, talk about how the crops were looking, that sort of thing. On this day, though, he gave me a look, then turned to Dad and asked, “Has he ever baled hay?” Dad grinned and said, “No, but he needs to learn.” And that was it—my fate was sealed. I didn’t have a say in the matter. One minute I was a kid riding shotgun with Dad, and the next I was knee-deep in hay bales. I was tossed straight into the fire!

The bales could weigh anywhere from forty to eighty pounds, depending on how dry the grass was. I was about ten years old then—skinny as a rail, green as could be, and without a lick of common sense when it came to farm work. I’d seen hay stacked on trailers before, but I’d never had a hand in building one of those towering loads myself. These days you can find step-by-step guides and YouTube videos on how to stack hay properly, but back then there was no such thing. I had to learn the hard way—on the spot, with no time to think it over.

The Hay Baling Process

Off we went—Lowell steady at the wheel of the tractor, and me bouncing along on the hay rack behind. The first bale thudded out of the baler, still warm from the press, and I dragged it to the back of the rack. Easy enough, I thought. Then came another, and another—each one hitting the wagon with a solid thunk.

The sun beat down mercilessly, the kind of heat that soaks into your skin and makes the sweat sting your eyes. I had no hat, and a pair of ragged cloth gloves Dad had tossed me like a parting gift. The air was thick with dust and chaff, bits of dried hay floating everywhere, scratching my arms and sticking to my sweaty shirt. Suntan lotion was unheard of back then. Besides, I was too tough for that!!

The bales kept coming, one after another, and each had to be lifted higher as the stack grew. My arms burned, my back ached, and soon I was falling behind. The stack leaned awkwardly, and before long a few bales slid off and tumbled to the ground. Out of the corner of my eye I caught Lowell’s face—tight with frustration, as if he was rethinking the whole idea of letting a scrawny twelve-year-old help.

But instead of hollering, he eased the tractor to a stop. Dust settled around us in the still air. He climbed down, brushed off his hands, and with the patience of a man who’d stacked a lifetime of hay, showed me how to lay the bales just right so they’d lock together and hold.

Stacking the Hay Bales behind the Baling Machine.

I felt like an idiot, but I finally figured it out. We started back up again, and I could sense he slowed things down. I was finally keeping up and making a reasonable stack. Once the wagon was stacked full, off to the barn we went.

Loading the hay into the barn.

I climbed up the elevator into the barn and braced myself for the steady stream of hay bales coming my way. Lowell worked the rack, sliding the bales onto the elevator, and up they came for me to stack inside the barn. This time, things went smoother—I’d found a bit of rhythm, and the stack began to rise neat and solid. When the rack was empty, we headed back to the field to do it all over again.

By the time the day was done, I was worn to the bone—hungry, parched, sunburned, and sore in places I didn’t even know could hurt. But I’ll never forget the moment Lowell handed me a check for my work. It wasn’t just the money—it was the feeling of having earned it. I loved the sound of the ink pin as he scratched out the amount on the check pad. No personalized checks in those days. It just said “City National Bank” and they figured it out. With plans already forming for a trip to Woolworth’s, the aches and blisters didn’t seem so bad after all. I would have several jobs over the years “haying” as we said. Always hard work. On some occasions the farmer’s wife would bring us lunch. Nothing tasted better. Sweet, cold lemonade, sandwiches or chicken, fruit and of course a piece of homemade pie or cake. I was living good!

Detasseling Corn

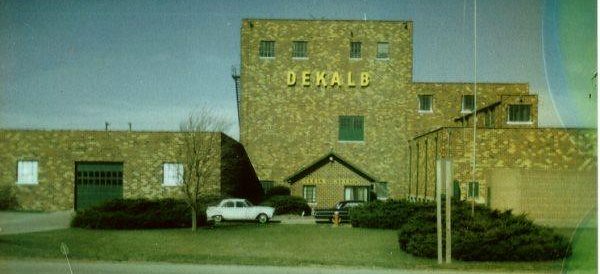

I spent a couple of summers working at the local DeKalb Seed Company, detasseling corn. Below is a picture of the actual Dekalb Seed Plant in Shenandoah. I am guessing the picture was taken in the late 1960’s. Its long gone now, but for many years it was a good source of steady employment. My brother worked there for a few years while earning money for college. As I recall they paid pretty well.

The Dekalb Plant in Shenandoah, Iowa

The detasseling process was simple enough—pull the tassels, those pollen-heavy tops, from certain rows so the plants wouldn’t fertilize themselves. This produced hybrid seeds with desired traits, such as disease resistance or higher yields. Machines came through first, snapping most of them off, but they never got everything. That’s where we came in—the summer youth labor.

We’d typically ride on a contraption like you see below. Our job was to pull any tassels that the machine missed. It wasn’t glamorous by any stretch, but it was steady summer work. My first crew boss was Roland Pully. His dad owned a store I think called “Standard Typewriter” where they sold paper, notebooks, pens, greeting cards, pencils, typewriters of course and that kind of thing. Roland was maybe 3 or 4 years older than me. He drove a small Mustang and would pick us (the crew) up each morning around 6:00 am to drive to the fields to begin the day. One year our crew consisted of me, Steve Hamilton and his cousins. I think they were from Chicago. They introduced me to the Rolling Stones. The music, not the band. They played the Stones 7 X 24. My first experience with Mick and Keith. I learned to hate the Stones after about 3 weeks of continual play on the cassette player or radio in the car.

We all packed into Roland’s car, no seat belts on of course and we would doze off while Roland drove. Most of the fields were in the Missouri River Valley near the Hamburg and Percival, Iowa area. Once at the corn field, Roland would fire up the machine, we would climb in the buckets and off we would go.

Riding Along Detasseling Corn

The work was kinda mind numbing….just ride along looking for tassels to pull. Most of the day we spent throwing pieces of corn at each other or giving Roland a hard time. The machines took care of most of the tassels. Hard to believe a company would pay kids to do this.

For me the highlight of the day was lunch. We would typically gather under a shade tree with the other detasseling crews. It was always interesting to see what everyone had to eat. I remember Loche Williams (RIP) used to bring raw hamburger for lunch. I can picture his face: long dark hair, always greasy, pimpled with scraggly whiskers. He was one of the few to wear his hair in a ponytail. Everyone said he was very smart, but it seemed kinda dumb to eat raw hamburger. No spoon or fork just used his hands to eat.

Mom always packed me a great lunch: raisins, PBJ or Bologna sandwich, crackers or chips and the best part of all Little Debbie Chocolate Cupcakes and a can of Shasta Root Beer or Cream Soda. I didn’t need a 5-star restaurant. This was living. It tasted so good. Since I always had a problem getting out of bed in the morning, I am quite sure I had no breakfast, so I was typically starving. Thank goodness mom took care of lunch!!

The detasseling season ran for maybe four to five weeks in the summer. I was always thrilled when mom drove me to the Dekalb building to pick up my paycheck. Man, I loved seeing my name on that check and as I recall it was pretty good money. Mom had enough foresight to make be put money into my savings account at the Security Trust and Savings Bank. I always held some back though for my trip to Woolworth or Gibsons!

Walking Beans

Somewhere between the invention of the combine and the rise of genetic engineering, Iowa farmers came up with a way to keep their soybean fields clean: bean walking. The practice was exactly what it sounds like—walking between rows of beans with a hoe or corn knife, pulling, chopping, or cutting out weeds that didn’t belong. The goal was simple: eliminate anything that stole nutrients or sunlight from the crop. Some folks also said weeds could clog the combine or lower the quality of the harvest, so there was extra incentive to keep fields tidy.

Beaning Crew

A typical setup meant each worker was responsible for six to eight rows, stretching out across fields that could cover hundreds of acres. We usually started at daybreak to beat the worst of the heat, but that came with its own price. The soybeans were soaked with morning dew, and after only a few dozen yards your shoes, socks, and pant legs were drenched. Before long, everything—right down to your underwear—was soggy. Man, I hated walking in wet shoes. Then, once the sun began to climb, that wet chill gave way to sweltering heat, and the whole experience turned downright miserable.

The upside to walking beans was that it paid pretty well, and out in the field we were our own bosses. I remember walking once with Rick Paulus—he lasted exactly one day before quitting. He got sick from the heat. He just gave up and sat down under a tree. Can’t say I blamed him; it wasn’t exactly enjoyable work. Over a few summers I ended up walking beans for Morris Freeze (Dad always called him “Burrrr”), the McLaren brothers, Delmus Gutchenritter, some of the Mahers near Imogene, and probably a few others I’ve since forgotten.

One of my most memorable experiences came while working for the McLarens near Farragut, Iowa. I had my first encounter with chewing tobacco. My buddy Randy Hunt, who by then was already burning through a pack of cigarettes a day, decided he needed a change. So, he hiked into Farragut—about a mile away—and came back grinning with a plug of Red Man. We all took a chew and headed down the rows.

The taste wasn’t bad at first—sweet, with a little kick that gave me a buzz. But nobody had bothered to explain the fine art of spitting, so instead of spitting I swallowed the juice. That turned out to be a big mistake. Before long my stomach was in knots, and I spent the rest of the afternoon stretched out under a shade tree, regretting every bit of that Red Man.

Shoveling Pig Shit

The main reason for cleaning hog pens was simple: keep the pigs healthy so they’d put on weight. Nobody talked about environmental concerns back then—it was all about money and making sure the hogs stayed strong and grew fast. Making bacon, you might say.

The McLaren brothers once hired me to help them clean their pens, and I went into the job a bit naïve. It didn’t take long to learn it was anything but glamorous. You’d step into the pen with a shovel, scrape out the manure, and either haul it off or, in this case, toss it into a growing pile just outside. The smell hit you like a wall—it clung to your clothes, boots, and even your hair. No matter how many times you washed up, you carried it with you the rest of the day, sometimes longer. I had clothes that were ruined, the stink just wouldn’t come out. now, when I drive past farmhouses sitting close to hog or cattle pens, I can’t help but wonder how folks manage to live with that smell day in and day out.

I had many other jobs growing up. I mowed lawns, “helped” Dad at his gas station, set up a Kool-Aid stand, sold magazines and Christmas cards door to door, shoveled snow (a job I’ll take any day over shoveling pig manure), and even tried running a bicycle repair shop—for about three days. All good experiences. I was lucky to have grown up during a time when a work ethic was valued and I could always manage to raise some pocket change or put a few bucks in the bank. Plus it was not big deal to go door to door to sell Christmas cards or whatever. Most people in town knew who I was and who my parents were. No way to get away with any kind of fraud back then. Ha, mom would have grabbed the fly swatter! Of all my jobs when I was young, I think my paper route offered the most enjoyment. More to come on that in “The Route Part 3”.

Leave a comment